| |

Italian Semester of Presidency of the European Union

EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINERVA

Quality for cultural Web sites

Online Cultural Heritage for Research, Education

and Cultural Tourism Communities

Parma, 20-21 November 2003, Auditorium Paganini

Margaret Greeves

(Assistant Director, Central Services Fitzwilliam Museum)

"IPR challenges for the Museum: a case study"

I am delighted to have this opportunity to present some of the

work of the Fitzwilliam Museum as a case study to this Minerva conference,

to earth our discussions in the real experience of an institution

whose twin purposes are preserving the collections in its care and

making them freely accessible for public education and enjoyment.

Throughout, we will be talking about editorially reliable, high

quality content, particularly images, and its delivery over the

Internet.

Our case study will illustrate the following statements from the

introduction to the Minerva programme, "Cultural heritage institutions

are in a key position to deliver the kind of unique learning resources

that are needed at all educational levels…[Such activity] challenges

the cultural institutions at their very core… Digitisation

is an expensive and technically complex enterprise in the long term

and this should not be underestimated…it requires noteworthy

investments and a strong commitment on the part of the individual

organisations that are depositories…A further commitment is

required to reduce digitisation costs [ ] and to develop new business

models. Among the principal challenges posed…is the conservation

of digital resources in the long term".

Underlying all that I shall say in this paper will be the conundrum:

how do we fund the activities that contribute to building the electronic

product? and the challenge, what innovative partnerships might be

developed between the cultural content providers and the commercial

publisher or other funding partner to sustain these developments?

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art museum of the University of Cambridge,

containing approximately half a million objects in the care of five

curatorial departments - Antiquities, Applied Arts, Coins and Medals,

Manuscripts and Printed Books and Paintings, Drawings and Prints.

All the collections are "designated" under a scheme which

identifies 50 collections in the UK of very significant national

importance. Under one roof we have museum collections, archives

and two libraries, spanning civilisations and millennia.

Until five years ago our use of images was conservatively traditional.

Our photographers took (and still take) colour transparencies for

publication in scholarly catalogues, general guides, exhibition

guides, teaching materials and for the illustration of research

by our own staff, members of the University of Cambridge and scholars

scattered across the world. Duplicate transparencies are deposited

with the Bridgeman Art Library and photographs and reproduction

rights are also sold directly by the Museum. Other photographic

activities are associated with conservation for condition reporting

and for

security purposes. The Fitzwilliam Museum Enterprises Company develops

products based on the collections using the transparencies - mainly

stationery goods - and generates revenue for the benefit of the

Museum. Again, unsurprisingly, we use images for public relations,

profile building and publicity purposes, to market the Museum and

its services, directly and through press and media coverage. Of

course, I do not need to tell this audience that the protection

of our copyright in our images is fundamental in this traditional

picture.

We did, however, give permission for our images to be included

in scholarly websites such as the Blake Archive and the Rossetti

Archive. These give access at two levels so that, using high resolution

images, art historians can make comparisons of different versions

of in vivo publications of the work of these two artists. We spent

much time negotiating watermark protection of the images, the inclusion

of statements of our copyright and direction back to the Fitzwilliam

for those who tried to print off images from the website.

The introduction at the Fitzwilliam Museum of an electronic Collections

Information Management System in 1999 rapidly drove a culture change.

With a grant form Resource, the Council for Museums, Archives and

Libraries to assist the Museum to address backlogs in documentation,

and following two years of careful planning, we introduced a collections

management database using Adlib software, and have been building

it up ever since, adding a curatorial department at a time and seeking

carefully to ensure consistency in the application of standards

and terminology.

Within 18 months of embarking on this project, however, the emphasis

shifted from information management to information sharing. The

drivers were technological - the ease of introducing a web interface

- and strategic. The expectations of users of museums such of ours,

the stimulation of government funding and the University environment

in which we work reinforced a new emphasis on access. In a very

short space of time we were driven to look up from our dedicated

inputting to create object records to consider who would use the

information, and how. The first step was intranet access, which

allowed the curatorial departments to look at one another's records

and non-expert staff members to share the information. This demonstrated

an unexpected ease of use - and usefulness. We then took a leap

and went public; we offered the information to our peers in other

museums and were surprised by their very positive response.

In other words, within less than two years of the start of our

project its purpose needed to be radically revised. Its new scope

was stimulating, exciting - and challenging. We found that our attention

to the application of standards, consideration of terminology and

the consistent use of fields across different types of materials

was increased. As accessibility became more important we sought

to define our several audiences, including those with disabilities

and special needs, and are currently evaluating the usability of

our website, the key interface to the information.

We have been rewarded with funding to collaborate in pilot projects,

as a content provider. We are preparing 100,000 records for harvesting

as metadata through the Open Archives Initiative (OAI). It will

be made available to the Higher Education environment through the

Arts and Humanities Data Service (AHDS) portal and the Archaeological

Data Service (ADS). It will also be harvested by 24-Hour Museum

which currently provides information on Museums' events and exhibitions

but is building a portal that will give users a taste of the objects

in the collections through thumbnail images and associated brief

records. In both projects we value the opportunity to collaborate

with partner museums and to benefit from the technological input

of the data providers.

Both projects have stimulated the Fitzwilliam Museum team to find

new routines - applying more automation to data cleansing, speeding

up the capture of images (see our Coins collections information

via www.fizmuseum.cam.ac.uk).

Interoperability throws up issues of standards, classification,

terminology, and for us, of consistency across different object

and collection types. The funding support for all of the work on

the database and allied projects described thus far is £500,000.

We have become more adventurous still and have developed a strategy

that examines opportunities for re-purposing knowledge for delivery

to different audiences in a variety of media and strives to take

forward their delivery simultaneously. We are nearing the completion

of Pharos, a web-accessible

structured database of information which links 300 key objects across

the Museum's departments. Many criteria were applied to the choice

of objects all of which are rich in their potential to offer connections

that empower the visitor to explore a variety of pathways, chronological

and thematic. The development of the content and the design has

taken three years and includes interactive demonstrations of techniques

of manufacture such as the creation of a fifteenth century, gold-ground

panel painting and the complex process of lost wax bronze casting.

The project was achieved for £100,000 but threw up pressing

IPR problems.

Now we are working on re-purposing the Pharos material and adding

to it in order to offer information within the galleries via handheld

computers. We will offer audio in several languages and for sight-impaired

visitors. We will use floorplans to orient visitors and diagrams

to locate works in their original context or reunite part works.

We also intend to extend our methods and materials videos to show

how coins were struck, Japanese wood blocks were printed, medieval

manuscripts illuminated and pots thrown.

Creative ideas abound but as our projects grow and become increasingly

complex, so the challenges increase. Our commitment to quality of

content and quality of access must be maintained but greater access

carries greater exposure to risk. Greater exposure of images on

the Web means greater loss of control, and this, in turn, will diminish

their value for exploitation in products to generate income. And

all this activity requires a level of investment that in our case

means constant searching for, applying for and obtaining grant support.

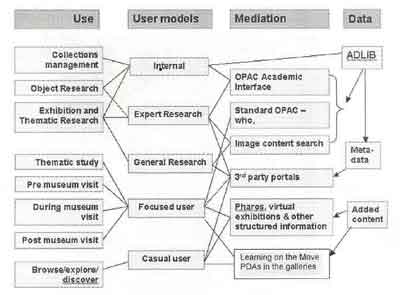

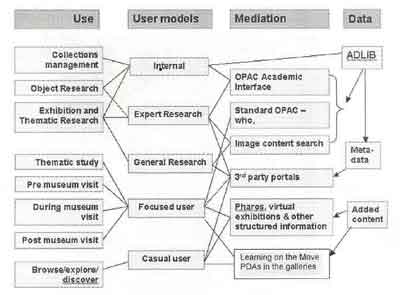

This diagram summarises how we see our project:

At the Fitzwilliam, on a very small scale, we have collected evidence

that shows clearly that users prefer images and that they provide

important information about cultural objects. Images enrich the

information and extend the creative uses to which it can be put.

The inclusion of images in publicity available electronic information

does cause us many copyright concerns and cost, however. So the

questions for us is how can we broker agreements with rights holders

for the use of images in educational materials at no cost? and how

can we protect our images from theft and misuse by others? How may

we find funding partners to share development costs who are willing

to do this with a light touch that will allow, indeed encourage

us to continue to experiment. In order to continue the development,

to sustain the products and to archive them securely, we would also

like to discover new models for cultural organisations to fund their

electronic access activities. Currently we seem to have four business

models: a) commercial sponsorship such as that by British Telecom

at Tate, b) the academic model that allows access at various levels

by means of a subscription (that is costly to collect), c) one which

relies on advertising and offers free access to the site but may

compromise the integrity of the institution and d) the current unsustainable

model where the institution and educational/national funders support

the development on a project by project basis.

In this rapidly developing area, cultural organisations with content

to provide need to test the market and need to find new funding

models. Is there a role for e-commerce? Should we rely on Europe?

|

|

|